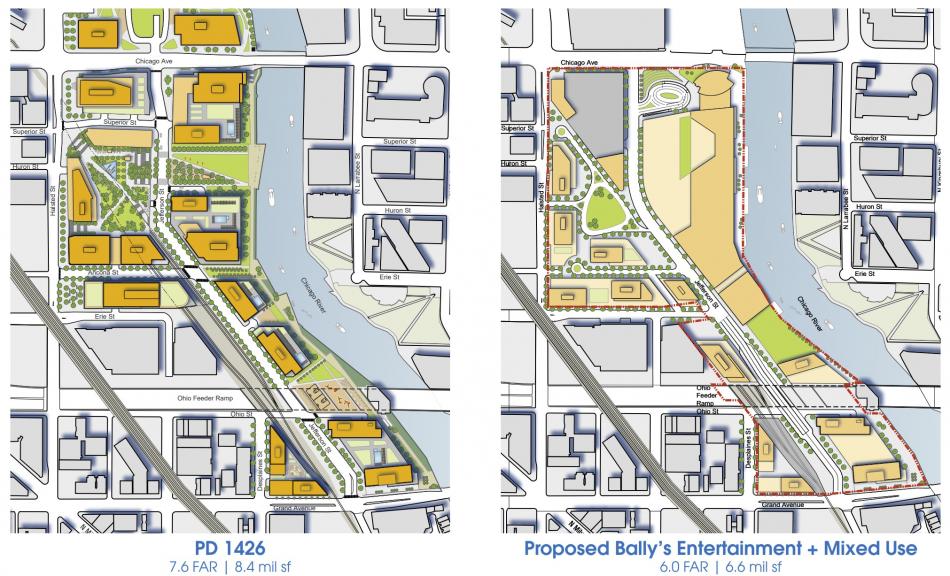

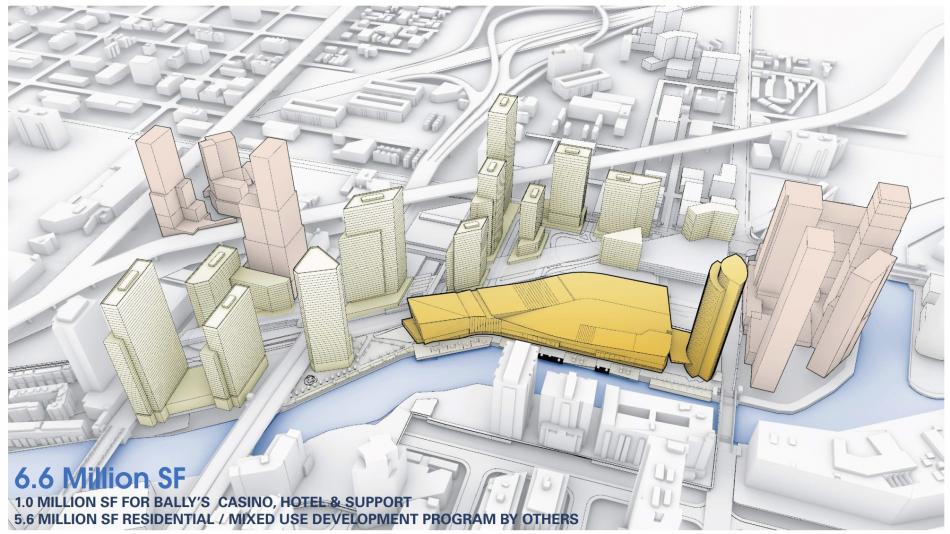

The Committee on Design has reviewed Bally’s plan for its upcoming casino at 777 W. Chicago. Sited along the Chicago River, the casino will replace the existing Chicago Tribune printing facility, reaching W. Chicago Ave to the north, W. Grand Ave to the south, and N. Halsted St to the west. As part of a revised River District masterplan, the casino will eventually be joined by a collection of mixed-use towers on the larger site.

Over the course of two hours, the committee spent more than an hour on their discussion after hearing a long-winded presentation on the multi-faceted, complex project. To approach our reporting with “relative” brevity, we will look at the project through the lens of the lengthy, exhaustive discussion that touched every inch of the proposal and turned it inside out.

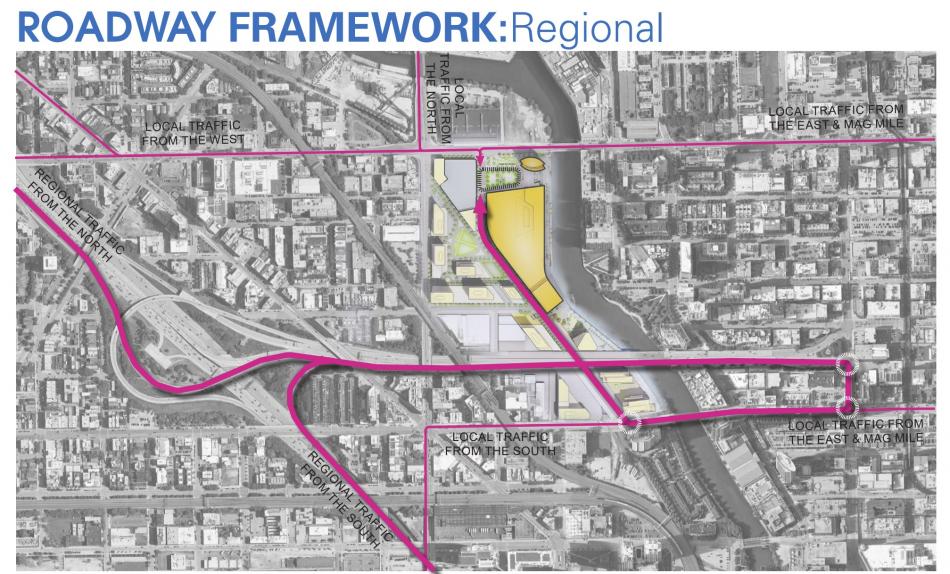

The discussion opened with questions from Leon Walker regarding the traffic plan. With Bally’s expecting about 3,000 cars to visit the site, their regional access plan calls for cars to exit the Kennedy Expressway using the Ohio Street feeder, turn right onto N. Orleans St, right again onto W. Grand Ave, and then onto the site from the south end. With only one lane of southbound traffic on N. Orleans St, Walker was concerned about congestion at that point. While they are working on an ongoing traffic study, this regional route is planned to avoid a high volume of cars on W. Chicago Ave and N. Halsted St in response to intense community pushback.

Renauld Mitchell pushed back on Bally’s and questioned whether remote parking could be considered to relieve the direct impact on the immediate vicinity. The representative from Bally’s said there is quite a lot of work going into determining the parking count, with their analysis seeing the casino as a regional site where many will commute to the casino, in turn requiring higher parking counts. Members of the committee challenged the notion of an increased need for cars, considering Chicago’s strong access to transit and the actual reality of the multi-modal nature of the area, considering access by pedestrians, bicycles, public transit, and rideshare.

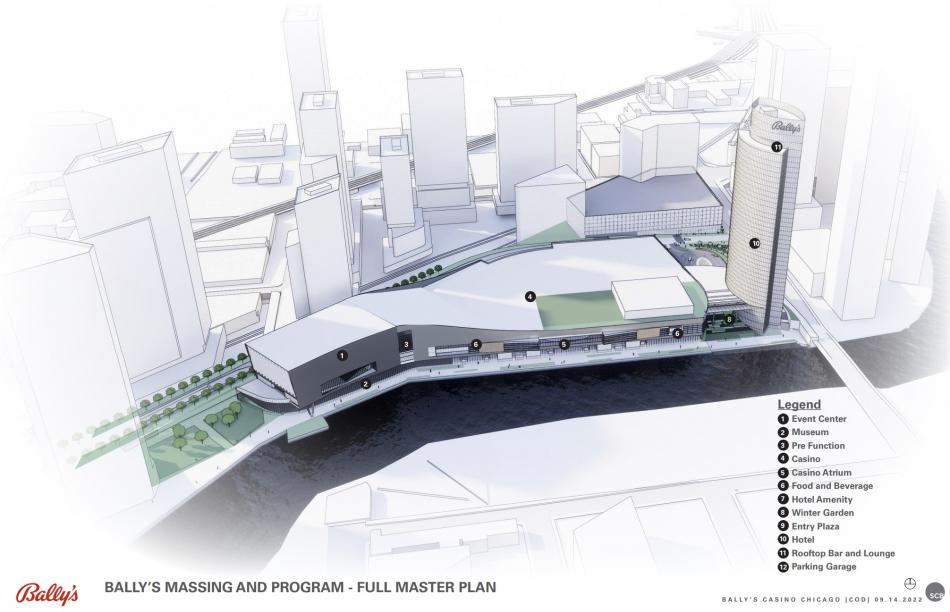

With SCB leading a larger group of architects and consultants on the design, the casino project will include a 500-foot-tall hotel tower at the north along W. Chicago Ave, a 3,000-seat theater further to the south, with the large casino building in between. Stretching multiple city blocks, the building will ultimately be enclosed with no windows along a newly constructed N. Jefferson St for almost 1000 feet.

Referencing the long, blank facade, committee members questioned the quality of the pedestrian experience along the new N. Jefferson St. According to the design team, regulations require the casino to be a contained space with a limited number of secured access points. Due to the nature of the site and adjacent railroad tracks from Union Pacific, the casino volume had to stretch and get longer to achieve the necessary size.

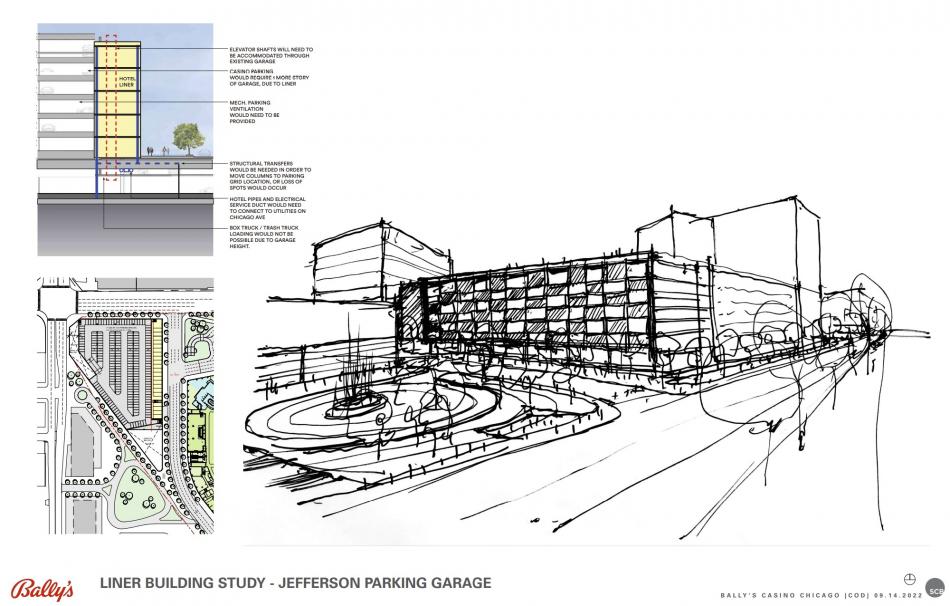

Jeanne Gang challenged the idea of the large casino floor plate and discussed how when a building typology is added into an urban setting, they need to transform. Gang suggested that they should think in section, potentially lifting the gaming floor one level above the street, freeing up the pedestrian realm for outward-facing retail and commercial spaces with flexibility of access to the river. More parking could be accommodated into the new street level behind the commercial space, reducing the need for the added parking structure that is planned to the west of the casino. The design team responded that they could look into, but the commercial space to line the parking that Gang mentioned is not currently part of the project’s program.

Brian Lee turned his focus to Bally’s, citing the fact that often clients restrict what architects can do with the design. Lee noted that the casino has been very contentious, and no neighborhood wants it, yet Bally’s has a prime riverfront site for the project. Lee challenged Bally’s with this as an opportunity for them to define what an urban casino can be and lead the way in terms of how it fits into the neighborhood. If done well, the new casino typology could create value not only for this phase, but also for the subsequent phases of development around the casino. Lee felt that the fundamental problem is the size of the single casino floor plate that is currently the design and urged Bally’s to think stronger and more creatively to reduce the footprint of the casino and create better connections through the site.

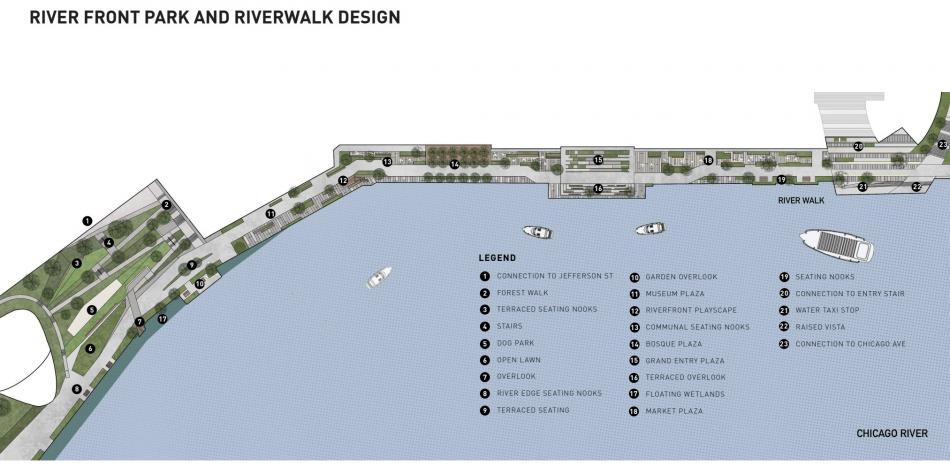

As designed, pedestrians and the public will be able to access the riverfront at the north end of the site from W. Chicago Ave and from a riverfront park south of the theater. A through connection between the casino and the theater also connects down to a museum at river level. Some restaurants that occupy multiple levels will reach down to the riverfront, activating that space along the water. A consideration brought up would be to, rather than orient all the outward facing program towards the water, reverse that and allow the river to be a seen, calm avenue and face the restaurants out towards N. Jefferson St to create a more vibrant pedestrian experience.

Reed Kroloff described the landscape plan as a string of pearls along the long stretch of frontage. Kroloff compared this approach to a suburban strip mall where everything is spread out and offered a different approach of clustering program to create moments of energy and activity along the river. The team responded that they pulled the program apart to try and activate the very long facade of the casino, but they have more work to do to finalize how that is executed.

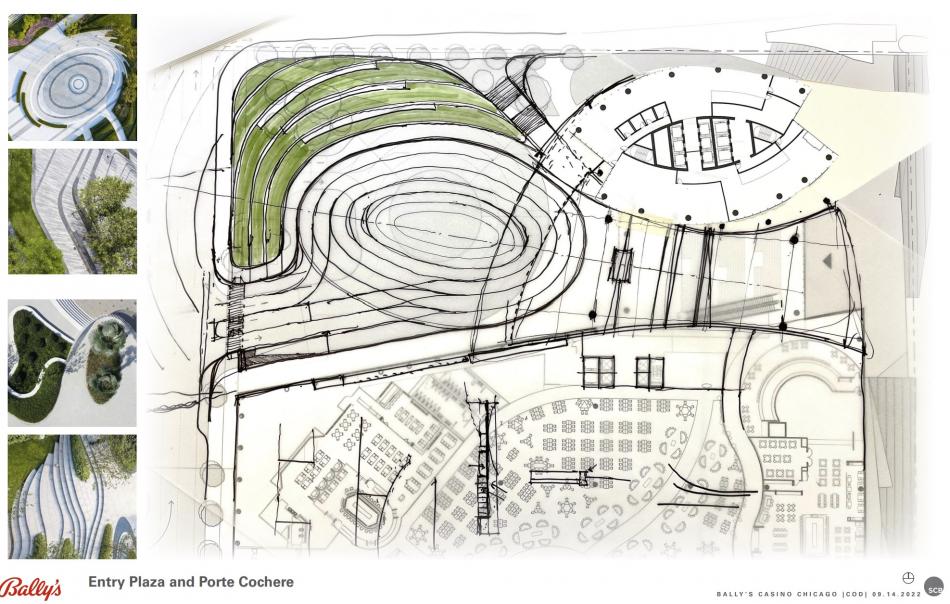

At the corner of W. Chicago Ave and N. Jefferson St, a public plaza would serve as a drop off and public connection into the site. Currently, the plaza would need to accommodate a grade change of about 8 feet up from the street. According to the project team, they are in conversation with the city as they reconstruct the Chicago Ave bridge and are looking into raising the height of the street to reduce the grade change from the street to the building.

Maria Villalobos chimed in to say that this plaza is not a true public space, seeing that the multiple purposes are there but it wouldn’t be a spot for the public to visit and spend time. Villalobos commented on how it is hard to get to the river and the current design makes it hidden from the public realm, asking whether the tower could be moved to give way to a bigger public space. The team responded that the location of the tower is flexible and could be rotated or moved to respond to the comments about the public space.

The team worked with DPD to place the tower as is shown, creating a gateway in relation to W. Chicago Ave and the planned development at the newly acquired site by Onni Group across the street.

Jeanne Gang commented that she likes the tower but wonders about the large parking structure across N. Jefferson St, as that becomes part of the gateway at the north end of the site as well. Rather than spending money on an expensive building to satisfy parking needs, Gang suggested that they relocate the parking into the casino volume with the aforementioned raised concept, freeing up that site for another luxury tower that can aid in the financials of the overall plan. According to Bally’s, they studied moving parking underground, but it became cost prohibitive which led to the current scheme of the above ground structure.

As the committee received hesitation from the project team, they defended their position and asked the project team to at least consider their comments rather than offer straight rejection. The representative from Bally’s assured them that the feedback is expected and welcomed as they work through the process. They have not taken lightly the context of the casino and the design team will attest to how much the design has gone through the wringer. The Bally’s representative said they have tried everything possible to integrate the casino and make it successful while ensuring practicality in the design. With contractual obligations to the city, Bally’s must ensure the economic success of the project and the current design is the best solution they have been able to come up with. At this point, redesigning the project is not feasible.

Leon Walker jumped back in to say that this discussion is of ideas and not all of them have to be incorporated. The committee is providing feedback and ideas for the project team to take and see what works while moving forward. Casey Jones responded to the adversity by saying that the committee is trying to lend their expertise to deliver a stronger project. Bally’s signed up to an RFP to meet the city’s challenge and they are trying to help Bally’s meet the challenge and they are aware of the complexities and issues that come along with the scale of development. Bally’s assured that they are reading between the lines to see how much could be incorporated while keeping the overall project practical.

After hearing the flexibility on the tower, Reed Kroloff chimed in to ask Bally’s if it is true that they can move the tower around but are not willing to shift any other parts. As the representative from Bally’s hesitated, Kroloff asked if they’re set on the L-shaped building that is roughly 1,000 feet long. The Bally’s rep said it is not a simple yes or no answer but due to the constraints of the site it would be hard to alter the footprint.

After a contentious two hours, the meeting adjourned with no steadfast answers on the future of the design. Since the Committee on Design is an advisory group, Bally’s is not legally bound to adhere to their comments but will need to answer to any takeaways DPD incorporates into the progression of the city approval process. While the project is far from typical, the plan will need to follow the typical procedural approvals needed by any Planned Development in the city. Further discussion and changes are expected before the proposal goes before the Chicago Plan Commission, Committee on Zoning and City Council. Work is projected to begin early next year and open in 2026.