The Commission on Chicago Landmarks voted unanimously to approve preliminary landmark status for a threatened West Loop building dating back to 1892. The commissioners also denied a permit to developers seeking to demolish the Queen Anne Victorian structure.

Located at the corner of Lake Street and Ogden Avenue, the four-story building was originally built as a Schlitz-branded tied house in anticipation of the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893. It most recently served as home to La Luce Italian restaurant, which closed in 2016.

In December, the property's current owner, Veritas LLC, received a permit from the city to tear down the building. The developer was days—if not hours—away from demolishing the historic tied house when the permit was swiftly revoked due to a clerical oversight.

The architecturally significant structure then went on a required 90-day demolition hold. The three-month hiatus allowed preservation groups to rally public support for sparing the building, and an online petition from Preservation Chicago gathered more than 8,100 signatures.

On Thursday the commissioners ruled that the West Loop property meets the criteria for individual landmarking and could be considered for inclusion in the city's existing Schlitz Tied House District, which includes nearly a dozen historic taverns spread across the city.

"Years from now I think people will look at it say 'of course this is a landmark,'" Ward Miller of Preservation Chicago told Urbanize on Tuesday. "Its architecture and design and scale speak to a wide audience, and we're so glad the city is recognizing and considering preserving that quality."

Chicago Department of Planning and Development

Chicago Department of Planning and Development

The team of developers that purchased the old La Luce building and the neighboring auto mechanic shop at 1385 W. Lake Street submitted letters to the city in opposition of the landmark designation.

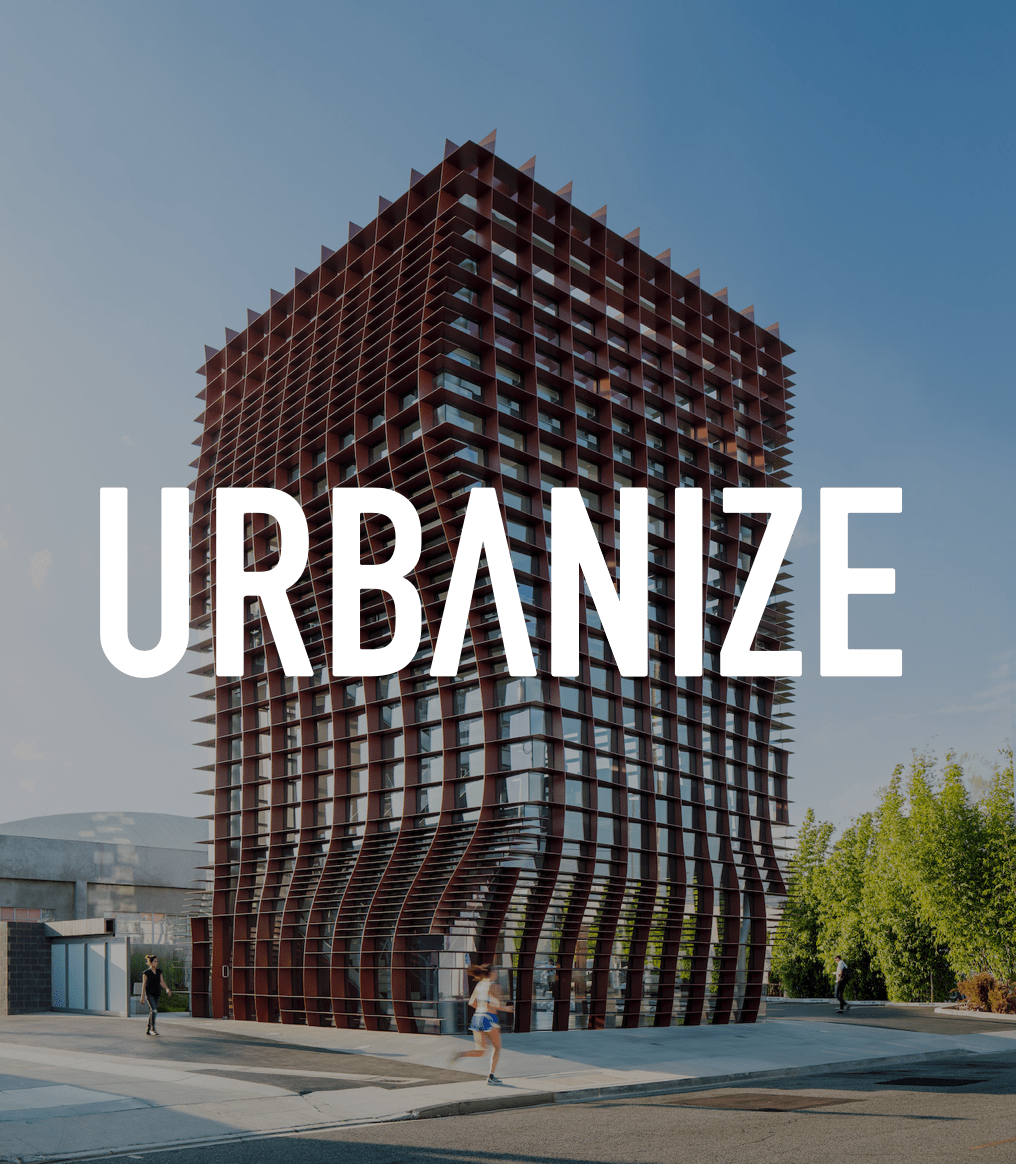

The property owners never presented their future plans to the public, but Sara Barnes, an attorney representing the developers, said the Lake Street site would have been developed as a "companion mixed-use complex" to the new apartment high-rise under construction at 1400 W. Randolph Street.

Barnes said her clients were now forced to focus on "mitigating the irreparable harm" that they would suffer if the city landmarked the property.

"The applicant has spent the last couple of months looking at ways to preserve and readapt the building or portions of the same into a larger development," Barnes said. "Such efforts have been deemed unachievable if the property is designated a Chicago landmark."

Chicago Planning Commissioner Maurice Cox voiced his support for the landmark designation and questioned why the building could not be repurposed and incorporated in a future development.

"We're here to evaluate whether this is worthy of landmark status," said Cox. "I think that is without question. The next question is why can't this asset be enveloped into a much more complex and layered interpretation of the site."

A preliminary landmark designation is the first step in the process to preserve the building. City staff will continue to research the property and submit a report before voting on the site's final landmark recommendation. The matter will then go before the city's Committee on Zoning and the full City Council for final approval.